Cooper Spur History

Welcome to our history page of the majestic North side of Mt. Hood, a relatively young mountain by geological standards. Mount Hood was born just 730,000 years ago, when volcanic pressure forced layer upon layer of earth and strata from near sea level to its peak of 11,240 feet. Take a moment to get to know the history of our beautiful mountain.

A Long History

A Tram on

Mount Hood?

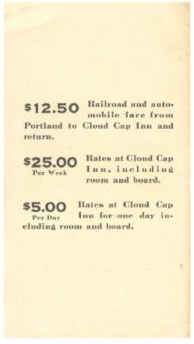

In 1926 a group of Portland and Hood River business men raised $83,000 for the expansion and improvement of the Cloud Cap Inn. Seattle architect E.A. Doyle made preliminary plans for a massive stone building with 32 rooms, a dining hall and lounge. More extensive sleeping areas could come when indicated by demand. The plan was ultimately approved- even after the regional forester turned it down because the full $100,000 cost had not been raised to start construction.

A trip to Washington D.C. to meet with, then Secretary of Agriculture, William M. Jardine promised hope. Following five years of study, the plan was approved, but with the country in depression, the project was never pursued. A part of the plan was a cable tramway from Cooper Spur to the very summit of Mt. Hood. In 1936 ground was broken on Timberline lodge.

Somewhere between the bottom of the climb and the summit is the answer to the mystery why we climb.

Greg Child

The Wy'east Indian Legend

Wy’east, a chief of the Multnomah peoples, loved a beautiful maiden named Loo-wit. Klickitat, chief of the Klickitat tribe, also loved her.

Loo-wit could not decide which of the handsome young chiefs she liked better so the two chiefs began to quarrel, flinging burning arrows at each other and laying waste to the land between.

The Great Spirit became angry at the squabbling chiefs and turned Wy’east into Mt. Hood in northwest Oregon, and Klickitat into Mt. Adams in southwest Washington. Loo-wit became Washington’s Mount St. Helens.

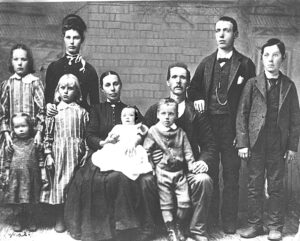

David Rose Cooper: Cooper Spurs' Namesake

The north side of Mt. Hood is steeped in history. The people of Hood River had long admired Mt. Hood, and there was a great urge to make it accessible. In the 1880s, several expeditions lead by Portland minister Thomas Lamb Eliot resulted in the discovery and naming of many of the area’s landmarks. Eliot’s Glacier, Lost Lake, Coe Glacier (after Captain Henry Coe), and Cooper Spur (named after David Rose Cooper) were among those discovered. Cooper had joined with Coe and Oscar Stranahan to form the Mount Hood Trail and Wagon Company to build a toll road and operate passenger service.

David Rose Cooper was very much the frontier type and spent a great deal of time exploring Mt. Hood- so much so that the prominent outcropping on Mt. Hood’s north face was named after him. He emigrated from Scotland in 1873 to Roseburg (Southern Oregon); but heard so much about the magnificent mountain overlooking the great gorge to the north, that he moved his family to Hood River in 1883.

In 1885, he and his wife Marian (who has the distinction of being the first white woman to live in the upper Hood River Valley) established the first “hotel” on the north side – a seasonal tent camp which included a cook tent, dining tent, and sleeping tents. The ten children in the family helped by splitting wood, stroking the fires, fishing for trout, and hunting deer for hotel fare.

It was Cooper’s idea to bring settlers and tourists into the Upper Hood River Valley and onto the mountain. It is thanks to him that we are all here today.

The Cooper "Tent Hotel" -circa 1888

Located near today’s Tilly Jane camp, this short-lived “hotel” offered guide services; leading guests across the high country on Mt. Hood’s north eastern slopes. The tent included a cook tent with a stove having an oven, dining tent with oil cloth covered table and white dishes, and sleeping tents; each furnished with a bed, a chair, and a table with a candle.

Marian Coooper handled the cooking while daughters Noma and Teena served as waitresses. Warren cut wood and kept the fires going as well as supplied fresh trout from trips down the mountain to Tony Creek. A milk cow furnished milk, cream, and butter. In 1889, a new lodge opened; The Cloud Cap Inn – ushering in a new era of tourism on the mountain.

Winter Recreation Paradise

The North face of Mt. Hood has been a source of inspiration and an outlet for recreation for those visiting and living in the Hood River Valley throughout history. A century ago – long before organized sports, electronic media, or the internet – families would recreate together by hiking and climbing to find new vantage points to view Wy’east. Along the way lessons were learned, friendships were forged, and legends were born.

It is, however, the snow for which the area has always been known. The early ascents of Mt. Hood all traversed across glaciers and required some technical climbing up snow chutes. The early explorers carried with them snow shoes and cross country skis to make climbing in variable conditions easier, as well as making the descent more thrilling and fun.

The first recorded north side ski trip was in February, 1890 when Will and H.D. Langille descended on lengthy Nordic skis. A snow Shoe Club was formed in 1902. It’s members would hike up the trail in their shoe shoes and then ride a toboggan back down. Photographs of this can be found on the walls of the Crooked Tree Tavern at Cooper Spur.

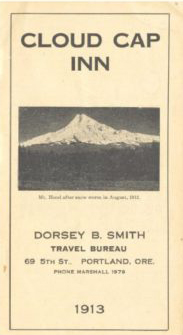

Cloud Cap - "The Grand Hotel" and 1st Summit

In 1889 the road to Cloud Cap was improved and the construction began on a “modern” hotel – the Cloud Cap Inn. The first few years of operation attracted mainly scientists, climbers, and tourists from many parts of the world. It wasn’t until Sarah Langille (sometimes called the “Lady of the Mountain”) agreed to take over Cloud Cap Inn in 1891 that the hotel became successful. Her warm hospitality set a tone for the lodge that made the visit of any guest a truly memorable experience.

Sara Langille’s sons, Will and Doug, were experienced mountain guides who lead climbing parties of guests to the summit. To so many of these guests in our history, the ascent of Mt. Hood was a once-in-a-lifetime experience. Upon return to the registry desk, the successful climbers were permitted to solemnly note the word SUMMIT by their names. On August 21st, 1891, Will and Doug accomplished the first documented ascent of Mt. Hood by the Cooper Spur route, describing it as being by far the most dangerous and difficult.

Even for the least adventuresome, a trip to Cloud Cap was very rewarding. The voyage would begin with the exciting coach ride up the mountain roads, taking approximately 5 1/2 hours from Hood River. The guest was blessed with the comforts of the hotel upon arrival; home-style meals, and the lively conversation before the fireplace. On clear summer days, the impressive rugged view of Eliot Glacier carried one’s mind to a level of philosophical bliss.

With Will and Doug guiding, and Sarah managing, the Cloud Cap Inn attracted thousands of recreational enthusiasts and vacationers. We are proud to be carrying on this strong tradition of home-made meals and mountain community.

Cooper Spur Ski Area History & Jack Baldwin

In 1927 the Hood River Ski Club cleared and built a ski jump on the steep hill (known as “Jump Hill” to the left of the chairlift (as you ride up). The tow motor was on the center of the hill, with tow rope running both above and below the lift shack, an unusual arrangement. It was somewhat underpowered. Too many skiers holding onto the rope all at once could halt the tow. The shack was removed in 1955 when the tow was lengthened, and the equipment was used to make a second tow.

By this time, the tow facilities had become a private operation by Jack Baldwin and George Howell. Ski Club members continued to do their part by manning the warm hut, providing ski instructions and ski patrol personnel. In 1956, the Hood River Junior Chamber of Commerce built the current loop road, running up from Cloud Cap road to the bottom of the ski hill, and back down again.

The ski club dropped out of all participation at Cooper Spur, and in 1970 Howell sold out to Baldwin. But Jack Baldwin was a man of vision, with a passion for skiing. Thanks to an SVA loan and some other support, in 1971 Baldwin expanded the facilities adding a 1,100 foot long T-Bar capable of handling 1,200 skies per hour. Night skiing was added and the ski area doubled in size from 20 to 40 acres. New buildings housed the warming hut and rental facility – and the original tow shack removed from the hill in 1955 was converted into the patrol shack.

Jack Baldwin set the vision, tempo and scope of operations at Cooper Spur for the next 30 years – and while their were other owners, the ski area operated much as it had in the past, continuing to appeal to families in search of affordable winter snow play. In addition to skiing and snowboarding, snow tubing was added to the area’s offerings. In 2001 Cooper Spur Ski Area was purchased by Mt. Hood Meadows.

In 2002, the T-Bar was replaced by a double chairlift, the rope tows were supplanted with newer versions, and the Alpine lodge was renovated with a new outdoor deck. Despite the improvements, lift ticket and tubing prices remained the same – a commitment to the affordable family snow play area envisioned by Jack Baldwin. The rest is history.

Alpinism is the art of going through the mountains confronting the greatest dangers with the biggest of cares. What we call art here, is the application of a knowledge to an action.

René Daumal

Mount Hood Geology

Mount Hood is Oregon's highest peak and an active volcano of the Cascade Range, located approximately 80 km (50 mi) east of Portland Metropolitan area.

Volcanic Beginnings

Mount Hood forms a prominent backdrop to the state’s largest city, Portland, and contributes valuable water, scenic, and recreational resources that help sustain the agricultural and touristic economies of the surrounding cities and counties. Volcanism occurs at Mount Hood and other Cascades arc volcanoes because of the subduction of the Juan de Fuca Plate off the western coast of North America.

This particular volcano has erupted episodically for about 500,000 years and hosted two major eruptive periods during the past 1,500 years. During both recent eruptive periods, growing lava domes high on the southwest flank collapsed repeatedly to form pyroclastic flows and lahars that were distributed primarily to the south and west along the Sandy River and its tributaries.

Quick Facts

- Location: North Central Oregon

- Latitude: 45.374° N

- Longitude: 121.695° W

- Elevation: 11,240 ft. (3,426 m)

- Volcano Type: Stratovolcano

- Composition: Andecite to Dacite

- Most Recent Eruption: 1865 CE

- Alert Level: High

Last Updated 11/6/2020

The last eruptive period began in 1781 BCE and affected the White River as well as the Sandy River valleys. As you may remember from history class, the Lewis & Clark Expedition explored the mouth of the Sandy River in 1805 and 1806 and described a river much different from today’s Sandy. At that time the river was choked with sediment generated by erosion of the deposits from the eruption, which had stopped about a decade before their visit. In the mid-1800’s, local residents reported minor explosive activity, but since that time the volcano has been quiet.

Present-day Mount Hood has grown episodically, with decades to centuries of frequent eruptions separated by quiet periods lasting from centuries to more than 10,000 years. During these eruptive periods the eruptive style has alternated between production of lava flows that have traveled as far as 12 km (7 mi) and lava domes that have piled up over vents on the steep upper slopes of the volcano: both kinds accompanied by tephra fallout.

On the steep upper slopes of Mount Hood, growing lava domes have repeatedly collapsed throughout history to form hot, fast-moving pyroclastic flows. The extreme heat from such flows can swiftly melt significant quantities of snow and ice to produce lahars that surge down river valleys, typically far beyond the flanks of the volcano.

Throughout Mount Hood’s history, swift landslides, called debris avalanches, of various sizes have occurred. The largest ones removed the summit and sizable parts of the volcano’s flanks- forming lahars that flowed to the Columbia River. Large debris avalanches occur infrequently and are usually trigged by eruptive activity. Smaller ones, not associated with eruptive activity, can occur more frequently. Typically these are triggered by failure of rocks that have been altered and weakened by acidic volcanic fluids or weathering.

Debris Avalanches

Rapidly moving landslides, called debris avalanches, occurred numerous times in the past when the steep upper parts of Mount Hood collapsed under the force of gravity. Small ones tend to be restricted to the upper flanks of the volcano, and large ones typically contain sufficient water to rapidly transform into far-traveling lahars.

About 1,500 years ago, a debris avalanche originating on the upper southwest flank of Mount Hood produced a lahar that flowed down the ZigZag and Sandy River Valleys. It swept over the entire valley floor in the Welches-ZigZag-Wemme-Wildwood area and inundated a broad area near Troutdale, where the Sandy flows into the Columbia River (a total distance of about 90 km (55 mi). The debris avalanche created the breached summit crater that has since caused most eruptive products to flow into the Sandy River basin while the Hood River basin remains sheltered.

More than 100,000 years ago, a much larger debris avalanche and related lahar flowed down the Hood River, crossed the Columbia River, and flowed several kilometers up the White Salmon River on the Washington side. Its deposits must have dammed the Columbia River, at least temporarily.

Glaciers

Glaciers and perennial snowfields on Mount Hood cover about 13.5 km² (5mi²) and contain more than 300 million cubic meters (nearly 400 million yd³) of ice and snow. The largest glaciers, Eliot and Coe on the north flank, are about 2.5-3 km (1.5 mi) long. Summer meltwater from the glaciers and seasonal snowpack provides irrigation water for the highly productive Hood River Valley fruit orchards and maintains flow in important fish habitats.

During the last ice age, glaciers radiated outward up to 15km (9.3 mi) in all of the major Hood drainages and filled valleys with hundreds of meters of ice. Glaciers were even more extensive during several older ice ages. Many lava flows were erupted during times of extensive glacier cover, which strongly influenced their distribution. During the Polallie eruptive period, pyroclastic flows from collapsing lava domes mantled glaciers with debris, which was transported by the glacier and dumped into moraines that formed at the glacier snout.

Whether during times of relatively restricted glacial cover (like now) or during ice ages, glaciers and snow provided a ready source of water to mobilize long-traveled lahars by pyroclastic flows swiftly producing large volumes of meltwater.

Lahars

Volcanic mudflows can be triggered by an eruption, develop during a landslide, or occur during periods of heavy precipitation and high runoff. These lahars sweep rapidly down valleys, picking up additional debris while eroding the channels in which they travel. As the flows run out, they deposit the mass of material that was gathered along the way.

Intense rainfall and sudden release of water from glaciers also cause small versions of lahars called debris flows. A rainstorm on Christmas day, 1980, triggered a landslide at the steep head of Polallie Creek on the east flank. The landslide transformed into a debris flow that scoured sediment from the creek’s channel banks and entered the East Fork Hood River, carrying a volume 20 times greater than the initial landslide. The debris flow temporarily dammed the East Fork. About 12 minutes later, the dam was breached and a flood surged down the river, destroying about 10km (6 mi) of Oregon Highway 35 – a total of $13 million in damage in 1980 dollars. One person was killed. Similar events have swept down most of the valleys on Mount Hood during the past century, but flows on White River, Newton Creek, Eliot Branch, and Ladd Creek have done the most damages to roads and bridges.

Future Eruptions

When Mount Hood erupts again, it will severely affect areas on its flanks as well as locations far downstream in the major river valleys that head on the volcano. The volcano ended a long dormant period (that had lasted about 10,000 years) about 1,500 years ago and has had two eruptive periods of lava-dome growth since. A significant eruption of Mount Hood would displace several thousand residents and cause billion-dollar-scale damage to infrastructure and buildings.

In addition to a large and growing nearby residential population, Mount Hood is a major recreation destination for skiing, climbing, hiking, camping, and many other types of tourism. There are also significant elements of transportation and electrical power infrastructure in the area, all of which would be affected by future activity and cause major economic losses in the region.

Seismic Monitoring

Mount Hood is one of the most seismically active volcanoes in the Washington and Oregon Cascades, and the most seismically active volcano in Oregon. In an average month 1-2 earthquakes are located by the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network (PNSN) within 3 miles of the summit. Most Hood earthquakes don’t actually occur directly beneath the volcano’s summit, but instead in one of the several clusters located 2-5 km west, southwest, and southeast of the summit.

The largest earthquake recorded in the vicinity of Mount Hood was a M4.5 in 2002 that was widely felt and followed 4 hours later by a M3.8 aftershock. M>3.0 Events have also occurred in 1989, 1990, 1996, and 2010. Earthquakes in these clusters tend to occur in swarms (defined as three or more located earthquakes in a single day) or “mainshock-aftershock” sequences.

The most notable such swarm occurred June 29th – August 18th, 2002, when 200+ earthquakes were located by the PNSN following the June 29th, 2002 M4.5 mainshock. Scientists believe that earthquakes in the clusters south of the summit occur on tectonic faults and aren’t directly related to volcanic processes occurring beneath Mount Hood. The largest earthquake recorded beneath the summit was a M3.5 in 1989 that was felt, with a M<3.0 event also occurring in 1982. In contrast to the southerly clusters, earthquakes directly beneath the summit rarely occur in swarms.

Mount Hood seismicity is monitored by the PNSN and CVO via a regional network that includes 5 seismic stations within 12 miles of the volcano.

Sources:

Cascades Volcano Observatory, “Mount Hood“, 04, December 2012. www.volcanoes.usgs.gov/volcanoes/mount-hood

Pacific Northwest Seismic Network, University of Washington, “Mount Hood- Seismicity“, November, 2020. https://pnsn.org/volcanoes/mount-hood#seismicity https://pnsn.org/volcanoes/mount-hood#seismicity

Crag Rats, “History of the Crag Rats” http://www.cragrats.org/about-the-cragrats/#history

history

Our Historic Lodge awaits

Ready to check out our historic lodge and scenic views? Book your stay in our rustic lodge to complete the adventure.

See Lodging Options